‘Zé Povinho looks from one side to the other and it stays – as always – the same’

Who doesn’t remember the bright red tomato-shaped bowls, turmeric-coloured pumpkin tureens or pitch-black swallows on the wall in your grannies’ home?

Who doesn’t remember the bright red tomato-shaped bowls, turmeric-coloured pumpkin tureens or pitch-black swallows on the wall in your grannies’ home?

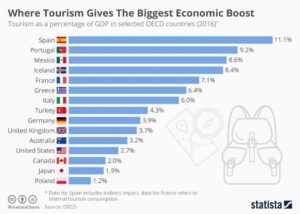

Portugal is the ‘hottest’ tourist destination in the world and even temperatures reached record highs this summer. The over a century old pottery of Bordalo Pinheiro has also become ‘hot’ and a ‘must-have for today’s millennials.’

Raphael Bordalo Pinheiro was a socialist, journalist, political caricaturist and publisher of satirical newspapers, who liked to mock the late 19th-century Portuguese society.

He created the popular cartoon Zé Povinho – a character of social criticism – who became the symbol of the ordinary Portuguese man.

He created the popular cartoon Zé Povinho – a character of social criticism – who became the symbol of the ordinary Portuguese man.

The figure’s main characteristic is the gesture of the cuff (‘Toma’), representing his facet of revolt and insolence.

Bordalo was also a sculptor and ceramist, who wanted to elevate everyday tableware to the design standards of porcelain.

Although by many called ‘kitsch’, his designs are firmly rooted in the Portuguese culture and natural environment. He made vegetables, flowers, insects, fish, and birds – in natural shapes and colours – look as real as possible.

![]() The Bordalo Pinheiro factory –since 1885 based in Caldas da Rainha, 75 km north of Lisbon – works with its own sculptors, who create new moulds from original pieces designed by Bordalo between 1884 and 1910.

The Bordalo Pinheiro factory –since 1885 based in Caldas da Rainha, 75 km north of Lisbon – works with its own sculptors, who create new moulds from original pieces designed by Bordalo between 1884 and 1910.

This year the company is opening its first shops abroad, in Paris and Madrid.

This year the company is opening its first shops abroad, in Paris and Madrid.

Half the one million pieces it sold last year – almost entirely handmade by the 250-strong workforce – went to buyers outside Portugal.

The Bordalo Pinheiro museum in Lisbon reunites much of his work although most of his ceramic pieces can be admired in Caldas da Rainha.

Bom fim de semana Have a great weekend

The vast majority of the

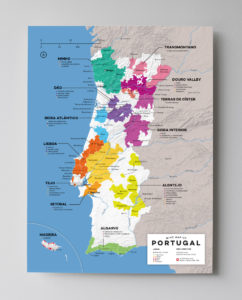

The vast majority of the  Portuguese drink the most wine worldwide, on average 1 litre per person per week.

Portuguese drink the most wine worldwide, on average 1 litre per person per week. Portugal’s wine culture developed in relative isolation for more than 2000 years. Many grape varieties – there are over 250 indigenous ones – do not grow elsewhere in the world.

Portugal’s wine culture developed in relative isolation for more than 2000 years. Many grape varieties – there are over 250 indigenous ones – do not grow elsewhere in the world. ‘To state that wine causes cancer is simply untrue’, says Georg Sandeman, chairman of the Portuguese Wine and Spirits Association (ACIBEV). ‘Northern countries want to impose their culture on us. In the north of Europe, people use to drink a lot in short periods of time (‘binge drinking’) and often without food. Here, wine is part of our culture, our gastronomy. Of course, excessive use should be reduced but not moderate consumption.’

‘To state that wine causes cancer is simply untrue’, says Georg Sandeman, chairman of the Portuguese Wine and Spirits Association (ACIBEV). ‘Northern countries want to impose their culture on us. In the north of Europe, people use to drink a lot in short periods of time (‘binge drinking’) and often without food. Here, wine is part of our culture, our gastronomy. Of course, excessive use should be reduced but not moderate consumption.’ The best advice, therefore, is to stick to the American Cancer Society’s

The best advice, therefore, is to stick to the American Cancer Society’s  Lisbon Airport is congested and overcrowded, a victim of a

Lisbon Airport is congested and overcrowded, a victim of a  Nevertheless, growth is skyrocketing and a further boost of 10 million passengers is expected over the next 5 years. The 75 years old airport certainly can’t cope, despite its clean appearance, tasty food, and nice shops.

Nevertheless, growth is skyrocketing and a further boost of 10 million passengers is expected over the next 5 years. The 75 years old airport certainly can’t cope, despite its clean appearance, tasty food, and nice shops. The ecological movement

The ecological movement  The ruling socialist party wants the government to speed up the

The ruling socialist party wants the government to speed up the  The reason for the amendment was the large-scale demonstration in May, when immigrants gathered before Parliament, expressing that they were treated like second-rank citizens, even though they paid tax and social insurance.

The reason for the amendment was the large-scale demonstration in May, when immigrants gathered before Parliament, expressing that they were treated like second-rank citizens, even though they paid tax and social insurance. ‘The law doesn’t promote the integration of immigrants, who work here for many years but are not treated as human beings’, says Timóteo Macedo, president of Solidaridade Imigrante (Solim). ‘Our Government argues, that we need more

‘The law doesn’t promote the integration of immigrants, who work here for many years but are not treated as human beings’, says Timóteo Macedo, president of Solidaridade Imigrante (Solim). ‘Our Government argues, that we need more  As of next week, a new

As of next week, a new  In most European countries domestic animals are tolerated in food courts.

In most European countries domestic animals are tolerated in food courts. According to an investigation in April by the Association for Consumer Protection (DECO), only

According to an investigation in April by the Association for Consumer Protection (DECO), only  Euthanasia continues to be a crime with prison sentences ranging from two to five years in “the land of the Maria’s” as Parliament

Euthanasia continues to be a crime with prison sentences ranging from two to five years in “the land of the Maria’s” as Parliament  Euthanasia – good death in old Greek – is

Euthanasia – good death in old Greek – is  ‘If boys have more privileges and sexual freedom in relationships than girls, there will be more social pressure to behave accordingly: strong, determined and protective’, reveals 18-year-old Catarina Machado. ‘

‘If boys have more privileges and sexual freedom in relationships than girls, there will be more social pressure to behave accordingly: strong, determined and protective’, reveals 18-year-old Catarina Machado. ‘ In a national survey among university students more than half stated to be victims of dating violence. Some were even threatened with death.

In a national survey among university students more than half stated to be victims of dating violence. Some were even threatened with death.

‘No, it is not okay’, mutters João. ‘We got a letter from the landlord the other day. Our contract expires in November. He wants to increase the rent from 300 to 800 euro a month and reduce the contract period to one year. I’ am sure he’ll increase the rent again next year.

‘No, it is not okay’, mutters João. ‘We got a letter from the landlord the other day. Our contract expires in November. He wants to increase the rent from 300 to 800 euro a month and reduce the contract period to one year. I’ am sure he’ll increase the rent again next year. ‘Where do you live?’, I ask

‘Where do you live?’, I ask Within five years rents in Lisbon increased by 36%.

Within five years rents in Lisbon increased by 36%. Housing is a priority for this government, that wants to build more affordable accommodation and has set aside 1,7 billion euros to give 26.000 needy families – half of them from Lisbon – a decent home within six years. It also intends to give municipalities the right to claim vacant properties for social habitation.

Housing is a priority for this government, that wants to build more affordable accommodation and has set aside 1,7 billion euros to give 26.000 needy families – half of them from Lisbon – a decent home within six years. It also intends to give municipalities the right to claim vacant properties for social habitation. Well, it’s a pity I’ am not one of those families and six years is a long time, especially at my age’, João replies.

Well, it’s a pity I’ am not one of those families and six years is a long time, especially at my age’, João replies. ‘It’s a shame how Portugal treats his refugees’, says Jose Manuel Pureza, MP of the Left Bloc (BE). ’The Portuguese government is – unlike many European countries – willing to accept more refugees. That’s positive. The problem, however, is the practical implementation.’

‘It’s a shame how Portugal treats his refugees’, says Jose Manuel Pureza, MP of the Left Bloc (BE). ’The Portuguese government is – unlike many European countries – willing to accept more refugees. That’s positive. The problem, however, is the practical implementation.’ ‘People are simply put somewhere and have no say at all in the conditions in which they are accommodated’, Vacchiano emphasizes. ‘As if a refugee doesn’t have a voice of his own. His educational background and profession don’t exist anymore. These are simply deleted.’

‘People are simply put somewhere and have no say at all in the conditions in which they are accommodated’, Vacchiano emphasizes. ‘As if a refugee doesn’t have a voice of his own. His educational background and profession don’t exist anymore. These are simply deleted.’ The granting of a residence permit by the SEF ( Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras) – Portugal’s immigration and border police – takes by and large 12 to 18 months. One can only apply for family reunification áfter obtaining the permit, which takes ‘at least another 5-6 months’, according to SEF.

The granting of a residence permit by the SEF ( Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras) – Portugal’s immigration and border police – takes by and large 12 to 18 months. One can only apply for family reunification áfter obtaining the permit, which takes ‘at least another 5-6 months’, according to SEF.