There are numerous terms to describe the wide array of far-right parties and their leaders. They are in one way or the other extreme right, radical right, populist, nativist, ultranationalist, authoritarian, neofascist, illiberal, ‘anti-woke’, anti-Islam, anti-immigration and Euro- and climate-sceptic.

The PopuList – an innovative project involving more than 100 political scientists from over 30 countries classifying Europe’s political parties and their ideologies – shows the steady increase of populist far-right parties in Europe from 1989 until 2022.

Chega (which means Enough) – at present the third-biggest force in Portuguese politics and led by André Ventura – is far-right and populist, with a strong focus on immigration and Islam.

Just like the PVV (Freedom Party) of Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (RN) in France and Victor Orban’s Fidesz in Hungary, who all believe that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of their own ‘native group.’

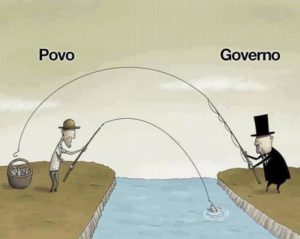

The picture is familiar. Mainstream parties are struggling with upcoming nativist movements that successfully exploit discontent with stagnating living standards. In Portugal, the sense of economic resentment has been deepened by an acute housing crisis, in part triggered by an influx of expats, who are lured through attractive tax concessions. Multiple corruption scandals have also played in Ventura’s hands.

Although the majority (87%) of the Portuguese want a democracy, nearly half (47%) are willing to support a government of a strong leader who does not have to worry about elections, according to ‘50 years of Democracy in Portugal’, a study recently carried out by the Institute of Social and Political Sciences (ISCSP) of the University of Lisbon.

’We can conclude that today the preference for democracy coexists with preferences for autocratic forms of government’, declared Conceição Pequito, one of the coordinators of the study. A more autocratic form of government ‘presupposes a weakening of the legislative and judicial power and poses a threat to the protection of political rights and civil liberties in a democratic liberal state.’

Of the respondents who prefer a Government with a strong leader, one-third are positioned on the extreme right and over 50% are neither interested in politics nor sympathize with a particular party.

Nowadays, the online presence of certain leaders is such that – in the eyes of voters – ‘they tend to be considered more important than parties.’

A situation that not only takes place in Portugal, and is exacerbated in the political communication made on social media.

Have a great weekend Bom fim de semana (Pic Sapo)

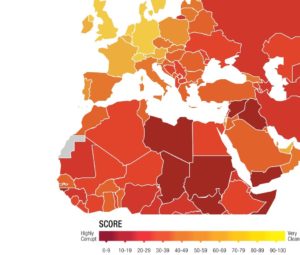

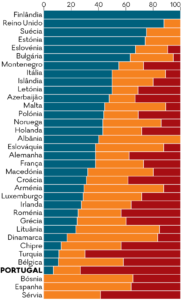

Perceived corruption in Portugal has for many years been just below the

Perceived corruption in Portugal has for many years been just below the  The low number of convictions and the fact that

The low number of convictions and the fact that  Corruption costs the country at least

Corruption costs the country at least  It is therefore not surprising that Portugal is the least compliant of 49 European countries in the fight against corruption. A report from the Council of Europe’s anti-corruption group (

It is therefore not surprising that Portugal is the least compliant of 49 European countries in the fight against corruption. A report from the Council of Europe’s anti-corruption group (