When you enter a hospital at night and hear a sick man groan, approach his bed, and if you have nothing left to give him, give him a smile – Dr Sousa Martins

After climbing Lisbon’s second hilltop, you will encounter a curious phenomenon. In a cosy little park called Campo Santana arises, amidst sturdy crowing little roosters and slow belly rocking ducks, a very special statue.

In its back the former Medical-Surgical School – now the Faculty of Medical Sciences of the New University of Lisbon – at its feet an immense heap of marble plates engraved with thanks for graces and miracles performed. Remarkable is the complete absence of religious symbols on these ex-votes. Was the figure in bronze on the pedestal a prestigious doctor, a saint or both?

In its back the former Medical-Surgical School – now the Faculty of Medical Sciences of the New University of Lisbon – at its feet an immense heap of marble plates engraved with thanks for graces and miracles performed. Remarkable is the complete absence of religious symbols on these ex-votes. Was the figure in bronze on the pedestal a prestigious doctor, a saint or both?

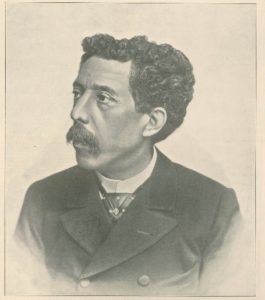

Born in a village of humble people some 30 km from Lisbon, he came at the age of 12 to the capital under the protection of his pharmaceutical uncle Lázaro and graduated in Pharmacy at the age of 21 and in Medicine two years later, both with the highest grades in his class. Became professor of General Pathology, esteemed for his professional skills, modest character and dedication to charity.

Dr Sousa Martins (1843-1897) gave special relevance to the doctor-patient relationship, teaching his students at the Hospital São José (St Joseph’s hospital) not only to treat but most of all to cherish the patients. One of his lessons was that if a doctor had nothing to relieve the suffering of the patient, he would still have a smile. Although famous as a pioneer in teaching, a brilliant scientist and doctor of the Royal Family, he never liked being credited with such notoriety and affirmed himself as ‘progressive and Freemason’.

Dr Sousa Martins (1843-1897) gave special relevance to the doctor-patient relationship, teaching his students at the Hospital São José (St Joseph’s hospital) not only to treat but most of all to cherish the patients. One of his lessons was that if a doctor had nothing to relieve the suffering of the patient, he would still have a smile. Although famous as a pioneer in teaching, a brilliant scientist and doctor of the Royal Family, he never liked being credited with such notoriety and affirmed himself as ‘progressive and Freemason’.

He was especially loved for the generosity with which he served the less fortunate, earning him the nickname Father of the Poor. He charged the rich large sums for their medical appointments but his poorest patient nothing, and often left money on their bedside tables along with recipes for medicines.

Sousa Martins gained enormous prestige in his fight against tuberculosis – which at that time reached epidemic proportions in Lisbon – and his name will forever be linked to Portugal’s first sanatorium in the Serra da Estrella, a mountainous region in the centre of the country.

Sousa Martins gained enormous prestige in his fight against tuberculosis – which at that time reached epidemic proportions in Lisbon – and his name will forever be linked to Portugal’s first sanatorium in the Serra da Estrella, a mountainous region in the centre of the country.

As a dedicated physician, he always was in direct contacts with his patients. The – at that time incurable – infectious disease he fought so hard during his medical career, coupled with a heart injury, eventually killed him.

As a dedicated physician, he always was in direct contacts with his patients. The – at that time incurable – infectious disease he fought so hard during his medical career, coupled with a heart injury, eventually killed him.

At 54, he committed suicide with an injection of morphine after confining to a friend ‘a doctor threatened with death by two diseases, both fatal, must eliminate himself.’

The brightest light in the kingdom went out, they said.

Enjoy your week Aproveite sua semana

Portugal prepares to vote in Sunday’s general election.

Portugal prepares to vote in Sunday’s general election. For the ruling Socialist party (PS) climate change adaptation is also needed. But that isn’t enough. The party defines concrete targets for 2030 and others for 2050, such as carbon neutrality. The PS wishes to reinforce the capacity of wind farms and – faced with extreme weather – extend forecasting and warning systems. Empowering farmers ‘to adopt good practices’ is also called for.

For the ruling Socialist party (PS) climate change adaptation is also needed. But that isn’t enough. The party defines concrete targets for 2030 and others for 2050, such as carbon neutrality. The PS wishes to reinforce the capacity of wind farms and – faced with extreme weather – extend forecasting and warning systems. Empowering farmers ‘to adopt good practices’ is also called for. The Left Bloc (BE) is in favour of a Climate Law, an Energy Base Law and a Ministry of Climate Action. The far-left party advocates the end of fossil fuel car production by 2025 and coal-fired power generation by 2023, in the meantime accelerating solar production. It also intends to ban cars from city centres and strives for free public transport, favouring investment in ‘rail mode’.

The Left Bloc (BE) is in favour of a Climate Law, an Energy Base Law and a Ministry of Climate Action. The far-left party advocates the end of fossil fuel car production by 2025 and coal-fired power generation by 2023, in the meantime accelerating solar production. It also intends to ban cars from city centres and strives for free public transport, favouring investment in ‘rail mode’. The millennium Animal and Nature party (PAN) – founded in 2009 – wants vegetarian meals at state-sponsored events, prevention of any exploitation of hydrocarbons and the closure of all coal plants by 2023. Furthermore financial benefits for cycling to work, measures to reduce car traffic, restrictions on night air traffic and the suspension of the construction of a new airport.

The millennium Animal and Nature party (PAN) – founded in 2009 – wants vegetarian meals at state-sponsored events, prevention of any exploitation of hydrocarbons and the closure of all coal plants by 2023. Furthermore financial benefits for cycling to work, measures to reduce car traffic, restrictions on night air traffic and the suspension of the construction of a new airport. However, the level of commitment of all six major parties is far too low, argues a group of independent citizens,

However, the level of commitment of all six major parties is far too low, argues a group of independent citizens,  The polls suggest António Costa’s Socialist party will win but fall short of an absolute majority in parliament.

The polls suggest António Costa’s Socialist party will win but fall short of an absolute majority in parliament.