‘We were the inventors of bad policy to buy and sell free and peaceful men as if buying and selling beasts’

( Padre Fernando Oliveira, 1555 )

During the Moorish occupation (8th – 12th century) Jews, Muslims and Mozarabs (as Christians were called) in Lisbon lived peacefully together. The three religions were socially integrated and participated fully in the city’s economic life.

After conquering the capital in 1147, Portugal’s first Catholic King Afonso Henriques guaranteed rights and conferred duties on the Mudéjars (Muslims living under Christian domination) in order to integrate the Islamic community into the kingdom. Religious freedom (with permission to build mosques), protection from the crown (with the obligation to work the kings’ lands) and the guarantee not to be harassed by Christians or Jews.

This balance began to fall apart in the 14th century, when the trend to isolate the non-Christian communities intensified, resulting in segregation laws and Jewish and Moorish quarters. Discrimination against Jews and Muslims grew steadily culminating in the Edict of Expulsion – signed by King Manuel I in 1496 – obliging these communities to convert forcibly to Christianity (and become Conversos) or to be expelled from the kingdom.

This balance began to fall apart in the 14th century, when the trend to isolate the non-Christian communities intensified, resulting in segregation laws and Jewish and Moorish quarters. Discrimination against Jews and Muslims grew steadily culminating in the Edict of Expulsion – signed by King Manuel I in 1496 – obliging these communities to convert forcibly to Christianity (and become Conversos) or to be expelled from the kingdom.

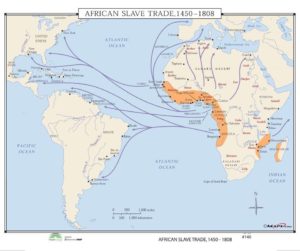

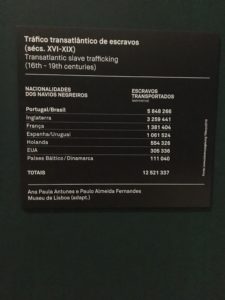

Around the same time Manuel I decided to give the monopoly in slave trafficking in the Portuguese empire to Lisbon. For two and a half centuries, a substantial part of the population in the capital – circa 10% – consisted of African slaves, performing the hardest tasks.

Black slaves lived outside the urban center in one of the western districts – called Mocambo – currently Madragoa.

The dirtiest work practiced by enslaved African women was that of collecting and carrying human waste, because of the weight of the excrement pot, its filthy content and the long distances they had to travel with it on their head. Not only in ancient Lisbon was the black women the hand that cleaned, even in our modern society this phenomenon continues to be very persistent!

The dirtiest work practiced by enslaved African women was that of collecting and carrying human waste, because of the weight of the excrement pot, its filthy content and the long distances they had to travel with it on their head. Not only in ancient Lisbon was the black women the hand that cleaned, even in our modern society this phenomenon continues to be very persistent!

The slavery of millions of Africans was justified by the argument that the Catholic faith had to be disseminated. The attitude of the church was that of saving the souls, representing a form of salvation through suffering.

When Portugal prohibited the slave trade in 1761, a consequence was the sale of African slaves to Brazil, resulting in a labour crisis in the country. It would take more than a century before slavery was also abolished on the other side of the ocean.

BOAS FESTAS HAPPY HOLIDAYS (pic PalPimenta/Observer)

There are roughly two ways to say tea in the world. One is like the English expression – thee in Dutch, tee in German or thé in French. The other is a variation of cha – chay in Russian, chai in Swahili or shay in Arabic. Both variations come from China. The words that sound like cha spread across the land, the tea saying spread over water.

There are roughly two ways to say tea in the world. One is like the English expression – thee in Dutch, tee in German or thé in French. The other is a variation of cha – chay in Russian, chai in Swahili or shay in Arabic. Both variations come from China. The words that sound like cha spread across the land, the tea saying spread over water. But the Chinese character for cha is pronounced as te in the Min Nan variety of Chinese, spoken in the coastal province of Fujian.

But the Chinese character for cha is pronounced as te in the Min Nan variety of Chinese, spoken in the coastal province of Fujian. Although it’s fairly commonly known that tea originated in China, it is far less known that it was a particular Portuguese woman, who inspired its popularity in England. Let’s go back to 1662, when

Although it’s fairly commonly known that tea originated in China, it is far less known that it was a particular Portuguese woman, who inspired its popularity in England. Let’s go back to 1662, when