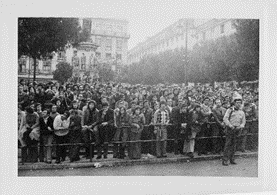

Retornados were not always received with open arms

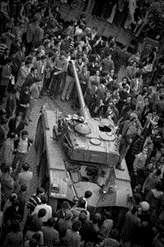

The Portuguese decolonization proposed by the Armed Forces Movement (MFA) was one of the main points of political divergence on the very day of the military coup 50 years ago.

‘Our intention was good but the change of the Program on the 25th of April, 1974 in the Command Post of the MFA in Pontinha – from which the reference to the right of peoples to self-determination and independence was removed by general António de Spinola – complicated things, explains captain Vasco Lourenço present at the time.

Spinola, former governor of Guinea and first (unelected) President of the Republic after the almost bloodless military coup was opposed to an ‘immediate’ granting of independence to the colonies and first wanted to hold popular consultations in the colonies. Nevertheless, on the 19th of July, the Council of State approved a constitutional law (Law 6/74), that ‘recognized the right of peoples to self-determination with all its consequences, including the right to independence.’

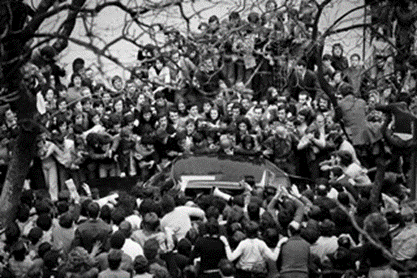

The declarations of independence of the former colonial territories in Africa, however, provoked a prompt and chaotic return of nearly half a million people to Portugal and outbreaks of long-lasting civil wars between the different liberation movements in Angola and Mozambique. Many did not actually return, because they were born in Africa and didn’t know Portugal.

The term ‘returned’ (retornado) was legally defined to determine who was entitled to State support.

Tens of thousands of returnees had to be housed in over 1500 hotels and pensions, that had to adept facilities to accommodate a much larger than usual number of guests, who brought sleep, hunger and trauma to their luggage. Large families, who had to fit in a single room, meant more cleaning and a lot more meals to serve. It costed the Portuguese State around 2.7 million euros per day.

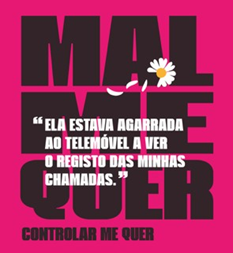

But the retornados were not always received with open arms in a country where an anti-colonial atmosphere prevailed after the Carnation Revolution.

Ana Simões, 67 – whose family decided to leave when they learned that there was an order to kill all the whites in the area where they lived in Angola – was 17 when she arrived in Portugal, where she found people shouting ‘that I should go back to my land, that I had stolen from the blacks in Africa and that I was stealing worker’s jobs here. I felt like they didn’t see me as Portuguese and that made me angry and sad at the same time.’

Maria de Oliveira, 65 – also has difficulty forgetting what she experienced after the 25th of Abril, first in Mozambique and later in Portugal. She and her family went through a shooting and at the age of 15 had a shotgun against her head. ‘Days later I was on my way to Lisbon without anything, not even a penny. When I see images of Gaza or Ukraine, I understand very well what these people are going through.’

Enjoy the 25th of April Boas Festas no dia 25 (pic Público)