‘We are often accused of being lazy’

Leaving the parental home is considered a milestone in the transition from childhood to adulthood. The reasons behind this step may vary from being materially independent to studying, working, moving in with a partner, getting married, or having children.

Portuguese men and women seem to remain forever young and stay with their parents for quite some time. In fact, making them the oldest to leave home in Europe.

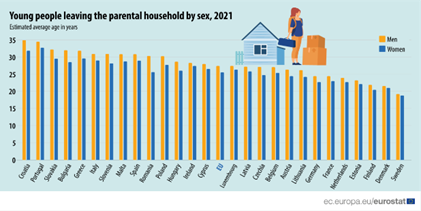

According to Eurostat the average age at which youngsters leave their home in the EU is 26,5 years but varies greatly between member states. Although Portugal (33,6 years) records the highest average age of young people leaving their parents’ home, Sweden has the lowest (19 years). A difference of more than 14 years!

This disparity reflects the various challenges young people face across Europe as well as cultural differences between countries.

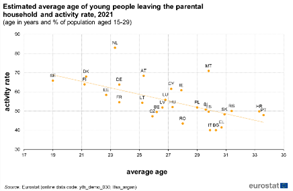

On average young women (25,5 years) move out of their parental household some two years earlier than men (27,4 years) and countries where young people leave home at an older age are more likely to have a lower force rate of participation.

For youngsters in Portugal, housing and income are the biggest challenges. The scenario is well known: buying a house is nearly impossible (prices have increased by 50% in the last five years), rents are far too high, wages do not grow at the same pace and there are more and more obstacles to accessing credit. Moreover, inflation is skyrocketing and energy prices increasing by the day.

Sociologist Lia Pappamikail believes that living with parents should not be perceived as a negative thing.

‘The two things can be reconciled: I can be perfectly independent and live at home with my parents. This does not mean that I am not autonomous; it means that I can do what I want and also have the resources to do it’

However, this does not apply to everyone explains Ana Lopes, a 26-year-old occupational therapist. ‘We are often accused of being lazy. But in reality, it is the external conditions that make the process of leaving home complicated. I get along very well with my parents but what I really want is my own space, a place to be myself and build my life’.

Susana Peralta, professor of Economics at the Nova School of Business and Economics, agrees with her. ‘We are less free when we live together. You are never as free as when you are alone’.

Enjoy The Week Boa Semana (pic Público/Sapo)

Last May, Joao Rodriguez – a 95% physically restricted and wheelchair dependent quadriplegic from Figueira da Foz – was happy his brother could bring him to Lisbon, to attend the nationwide

Last May, Joao Rodriguez – a 95% physically restricted and wheelchair dependent quadriplegic from Figueira da Foz – was happy his brother could bring him to Lisbon, to attend the nationwide  Eduardo Jorge – quadriplegic, bedridden since age 28 and living in a nursing home – requires continuous care for 24 hours a day. He owns a house and wants to be cared for at home, but doubts if he will get there the 24/7 support, he desperately needs. He demonstrated last week outside

Eduardo Jorge – quadriplegic, bedridden since age 28 and living in a nursing home – requires continuous care for 24 hours a day. He owns a house and wants to be cared for at home, but doubts if he will get there the 24/7 support, he desperately needs. He demonstrated last week outside  The intention of the government is to subsidize each centre with

The intention of the government is to subsidize each centre with  In addition to a greater autonomy, pressure groups demand more jobs and better accessibility of public buildings and

In addition to a greater autonomy, pressure groups demand more jobs and better accessibility of public buildings and  The Trade Union Association of Portuguese Judges (ASJP) declared in an open letter to the Minister of Justice this year, that at least 55

The Trade Union Association of Portuguese Judges (ASJP) declared in an open letter to the Minister of Justice this year, that at least 55  De belangrijkste handicap van Lissabon voor mensen met een beperking is, dat de stad – net als Rome – op zeven heuvelen is gebouwd en bezaaid met trappen. Rolstoelen houden niet van hellingen en al helemaal niet van trappen.

De belangrijkste handicap van Lissabon voor mensen met een beperking is, dat de stad – net als Rome – op zeven heuvelen is gebouwd en bezaaid met trappen. Rolstoelen houden niet van hellingen en al helemaal niet van trappen. De linkse regering wil mensen met een beperking – die vaak in instellingen verblijven – meer autonomie geven door hen in hun eigen vertrouwde omgeving te laten wonen.

De linkse regering wil mensen met een beperking – die vaak in instellingen verblijven – meer autonomie geven door hen in hun eigen vertrouwde omgeving te laten wonen. Mocht Rob alsnog besluiten te gaan, dan wacht hem een verassing. Er is namelijk pas een wet aangenomen, die niet toestaat dat mensen met een beperking in een rij moeten wachten, ook niet voor een restaurant.

Mocht Rob alsnog besluiten te gaan, dan wacht hem een verassing. Er is namelijk pas een wet aangenomen, die niet toestaat dat mensen met een beperking in een rij moeten wachten, ook niet voor een restaurant.