‘A country that hesitates over the care of those giving birth is a country without direction’.

The crisis hitting Obstetric services in Portugal drags on this summer with limited services and even straightforward closures of State (National Health Service) Maternity Units during the weekends, including hospitals of reference in the Greater Lisbon area.

Pregnant women either make do on their own or have to go to private hospitals, where more than half of the doctors specializing in obstetrics are working.

The country’s tabloid Correio da Manhã commented that ‘something is wrong in a country with a shrinking population, that cannot guarantee the minimum conditions for its babies to be born safely and obliges pregnant women with obstetric emergencies to travel irresponsibly long distances because the closest maternity bloc is closed due to lack of doctors.

The reason for the public consternation was the recent loss of a baby whose 41-year-old mother in labor was forced to travel 100 km before reaching a functioning maternity hospital.

The Nurses’ Order and the NGO Observatory for Obstetric Violence are urging the Health Minister Martha Temido to put in place the European directive to give specialist nurses – who have the skills required to oversee low-risk pregnancies in primary care centers – the autonomy they are calling for, at the same time reducing the total dependence on hospital care.

There are currently 3,182 specialist nurses whose potential is being wasted in this regard.

The lack of medical specialists and obstetric care is not only affecting perinatal care but also maternal mortality, which has reached its highest level since 1982. Last year – with 85,000 live births – 17 pregnant women died due to complications of pregnancy ( 8 during pregnancy, 1 during childbirth, and 8 within six weeks after delivery). Thirteen occurred in hospital, a mere 3 were 40 years or older.

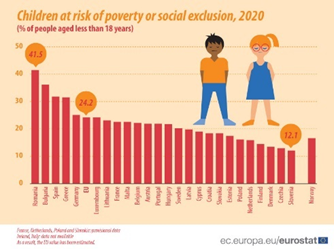

Moreover, instrumental vaginal birth (with help of a vacuum extractor or forceps) is three times (31%) higher in Portugal than the European average (11%). Episiotomies (incisions made in the perineum to enlarge the birth canal) are also more frequent and amount to 41%, twice the European average (20%).

These are the main conclusions of a European study including more than 21.000 women from 12 countries and published in the February issue of The Lancet Regional Health – Europe.

‘We have an exacerbated use of the these unnecessary practices similar to countries with a poor quality of care’, declared Raquel Costa, one of the researchers at the Institute of Public Health at the University of Porto.

Enjoy the week Boa semana (pic Público/Sapo)