Cesariny

‘Em todas as ruas te encontro – On every street I encounter you’

(from: Pena Capital, 1957)

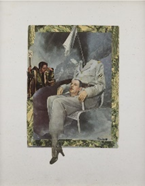

To celebrate the centenary of the birth of Mário Cesariny de Vasconcelos (1923-2006), the country will mark a year of reflection on the work and life of its most famous surrealist poet, activist, and painter.

Last month the festivities reached the capital with a major exhibition ‘O Castelo Surrealista’ (the surrealist castle) at the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT) – until the 18th of February. Some new publications are also in the pipeline as well as a series of lectures, concerts, and performances throughout the country.

At a very young age, Mário Cesariny learned chiseling to continue his father’s trade, goldsmithing. He didn’t like the subject and entered the Lisbon Conservatory (piano major). During the war, he was shown surrealist magazines from Paris by friends and became captivated by those anomalous texts and images.

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, he was initially interested in neo-realism, a movement dominated by the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP), that positioned itself as a viable alternative to the official art of the fascist Estado Novo (New State) of Salazar. But he left the movement soon after because of its fidelity to the representation of people in paintings and its stylistic dictates, including the obligatory use of figuration.

In 1947, he got the chance to spend some time in Paris, where he visited the International Exhibition of Surrealism organized to reinvigorate the surrealist movement that had been on the verge of disappearing during the war. There he met André Breton, the founder and leader of the French surrealists, and later that year founded the Portuguese Surrealist group (Os Surrealistas).

In 1950, his debut poetry collection ‘Corpo visível’ (visible body) was published outside the censorship of Salazar’s dictatorship. He lived in London and Paris, sometimes for longer periods, to be free of the intrusiveness of the PIDE (secret police) as they kept an eye on him because of his homosexuality and political ideas.

‘Surrealism is a way of transforming life and the world’, he used to say.

‘It is one of the two great revolutions of the 20th century, the other is Lenin’s.’

Only in 1961, when the repressive regime had somewhat softened, his poems were published by an established publisher in Portugal. In 1974 – when the Carnation Revolution liberated the country from the fascist terror – he participated in the Poetry International festival in Rotterdam, the Netherlands after which all his work was published and he was able to make trips to Spain, England, the US, and Mexico.

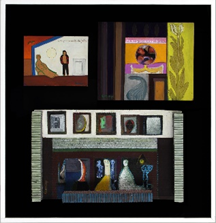

Cesariny was first and foremost a great poet. Public recognition for his pictorial work came later with the EDP Grand Prize for painting in 2002. That same year, a major retrospective exhibition of his paintings and other visual work was held in several Portuguese museums and an oeuvre catalog was published.

But he also was an excellent translator of poetry, translating work from Rimbaud, Novalis, and Breytenbach.

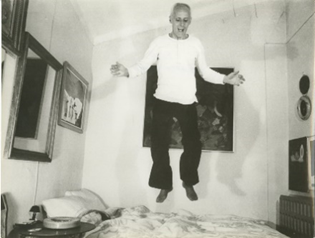

Happy Holidays Boas Festas (pic Público/Zucamag)