Before the pandemic, the Portuguese economy grew at a faster pace than the eurozone and the country ranked 28 on the list of wealthiest nations, despite its low rates in advanced education (50% of the population has only primary education; the highest percentage in Europe!) and average income (807 euro/month).

When the Chinese president Xi Jinping visited Portugal 18 months ago, the country willingly signed a multitude of cooperation agreements. At that time the socialist minority administration felt positive about the so-called ‘new Silk Route’.

In the meantime, its ‘golden visa program’ had opened the floodgates to Chinese buying up all sorts of property, banks, hotels and insurance companies.

But the tide has turned. The current public health crisis will drive a contraction in real GDP, and the long-lasting impact of the coronavirus on tourism will prevent a quick recovery in 2021.

An important economic lesson learnt, is to reduce dependence on imports from China. ‘This is the moment for Portugal to return to producing much of what we have been habitually importing’, Prime Minister António Costa declared.

To support the economy and prevent a debt crisis, Portugal can get 26.361 billion euros – 15.526 billion in grants and 10.835 billion in loans – from the European Economic Recovery Fund.

In order to access these funds, the country has to commit to the implementation of a reform plan program approved by the European Commission and the majority of the EU Council.

The government intends to use these assets to decarbonize the economy and reduce the imports of natural gas by developing an industry around hydrogen.

A European hub of ‘green energy’ (so-called because it is produced from renewable energy) close to Sines, one of the country’s major ports.

Sines is the perfect choice with its coal and oil-fired plants being disabled, and the network of existing gas pipelines 70% ready to distribute hydrogen. ‘Green hydrogen will be very cheap to produce and boost qualified employment’, says João Pedro MatosFernandes, the Minister for the Environment and Energetic transition

Another strategy to overcome the economic crisis caused by the pandemic, is to transform the country into ‘a cluster of industrialisation’, explains Minister of Foreign Affairs Augusto Santos Silva. ‘Portugal wants to be at Europe’s reindustrialisation forefront. We are talking here about textiles, clothing, shoes but also engineering, pharmaceuticals and agrifoods’.

He stressed that the country has important assets it can use like, qualified human resources, low wages, technology, quality of services and dominance in renewable energies.

Stay healthy Fique saudavel (pic Público/Sapo)

Portugal prepares to vote in Sunday’s general election.

Portugal prepares to vote in Sunday’s general election. For the ruling Socialist party (PS) climate change adaptation is also needed. But that isn’t enough. The party defines concrete targets for 2030 and others for 2050, such as carbon neutrality. The PS wishes to reinforce the capacity of wind farms and – faced with extreme weather – extend forecasting and warning systems. Empowering farmers ‘to adopt good practices’ is also called for.

For the ruling Socialist party (PS) climate change adaptation is also needed. But that isn’t enough. The party defines concrete targets for 2030 and others for 2050, such as carbon neutrality. The PS wishes to reinforce the capacity of wind farms and – faced with extreme weather – extend forecasting and warning systems. Empowering farmers ‘to adopt good practices’ is also called for. The Left Bloc (BE) is in favour of a Climate Law, an Energy Base Law and a Ministry of Climate Action. The far-left party advocates the end of fossil fuel car production by 2025 and coal-fired power generation by 2023, in the meantime accelerating solar production. It also intends to ban cars from city centres and strives for free public transport, favouring investment in ‘rail mode’.

The Left Bloc (BE) is in favour of a Climate Law, an Energy Base Law and a Ministry of Climate Action. The far-left party advocates the end of fossil fuel car production by 2025 and coal-fired power generation by 2023, in the meantime accelerating solar production. It also intends to ban cars from city centres and strives for free public transport, favouring investment in ‘rail mode’. The millennium Animal and Nature party (PAN) – founded in 2009 – wants vegetarian meals at state-sponsored events, prevention of any exploitation of hydrocarbons and the closure of all coal plants by 2023. Furthermore financial benefits for cycling to work, measures to reduce car traffic, restrictions on night air traffic and the suspension of the construction of a new airport.

The millennium Animal and Nature party (PAN) – founded in 2009 – wants vegetarian meals at state-sponsored events, prevention of any exploitation of hydrocarbons and the closure of all coal plants by 2023. Furthermore financial benefits for cycling to work, measures to reduce car traffic, restrictions on night air traffic and the suspension of the construction of a new airport. However, the level of commitment of all six major parties is far too low, argues a group of independent citizens,

However, the level of commitment of all six major parties is far too low, argues a group of independent citizens,  The polls suggest António Costa’s Socialist party will win but fall short of an absolute majority in parliament.

The polls suggest António Costa’s Socialist party will win but fall short of an absolute majority in parliament. Five years after the peak of its economic crisis, Portugal’s future looks bright. There is more confidence, more consumption and there are more young people in college.

Five years after the peak of its economic crisis, Portugal’s future looks bright. There is more confidence, more consumption and there are more young people in college.

The country’s workforce is relatively

The country’s workforce is relatively

If you are what you eat (drink, smoke) or love (males, females, yourself), then countries certainly aren’t the same. There are after all innumerous appetites and lifestyles. For example, health club membership is twice as high in Spain and three times higher in Denmark.

If you are what you eat (drink, smoke) or love (males, females, yourself), then countries certainly aren’t the same. There are after all innumerous appetites and lifestyles. For example, health club membership is twice as high in Spain and three times higher in Denmark. Portuguese people take 4744 steps a day, far less than the Chinese in Hong Kong or even their Spanish neighbours. Two-thirds are not physically

Portuguese people take 4744 steps a day, far less than the Chinese in Hong Kong or even their Spanish neighbours. Two-thirds are not physically  Portuguese adore cars – one in every two owns one – and use them every day. For everything: commuting, shopping, and outings. Unfortunately, these motorists hardly ever use public transport and are keen to make

Portuguese adore cars – one in every two owns one – and use them every day. For everything: commuting, shopping, and outings. Unfortunately, these motorists hardly ever use public transport and are keen to make  Apparently not. Portuguese people love their culture and are– besides Fado, Football, and Fatima – fond of grilled sardines, Pessoa, Saramago, sunny weather and popular saints. They also

Apparently not. Portuguese people love their culture and are– besides Fado, Football, and Fatima – fond of grilled sardines, Pessoa, Saramago, sunny weather and popular saints. They also  The most stunning, however – at least according to the Observer – are the eyes of their men. Wherever you are in the world, you should look at their

The most stunning, however – at least according to the Observer – are the eyes of their men. Wherever you are in the world, you should look at their  Portuguese drink the most wine worldwide, on average 1 litre per person per week.

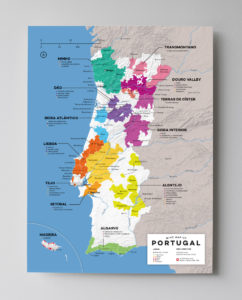

Portuguese drink the most wine worldwide, on average 1 litre per person per week. Portugal’s wine culture developed in relative isolation for more than 2000 years. Many grape varieties – there are over 250 indigenous ones – do not grow elsewhere in the world.

Portugal’s wine culture developed in relative isolation for more than 2000 years. Many grape varieties – there are over 250 indigenous ones – do not grow elsewhere in the world. ‘To state that wine causes cancer is simply untrue’, says Georg Sandeman, chairman of the Portuguese Wine and Spirits Association (ACIBEV). ‘Northern countries want to impose their culture on us. In the north of Europe, people use to drink a lot in short periods of time (‘binge drinking’) and often without food. Here, wine is part of our culture, our gastronomy. Of course, excessive use should be reduced but not moderate consumption.’

‘To state that wine causes cancer is simply untrue’, says Georg Sandeman, chairman of the Portuguese Wine and Spirits Association (ACIBEV). ‘Northern countries want to impose their culture on us. In the north of Europe, people use to drink a lot in short periods of time (‘binge drinking’) and often without food. Here, wine is part of our culture, our gastronomy. Of course, excessive use should be reduced but not moderate consumption.’ The best advice, therefore, is to stick to the American Cancer Society’s

The best advice, therefore, is to stick to the American Cancer Society’s  Patients have to wait 3 years to see a urologist in Vila Real or an ENT specialist in Leiria and 2 years to obtain an appointment with a cardiologist in Guarda. These extremes not only occur in the countryside, as the waiting list for a neurological consultation at Amadora Sintra – one of the biggest state hospitals in the country – exceeds more than a year.

Patients have to wait 3 years to see a urologist in Vila Real or an ENT specialist in Leiria and 2 years to obtain an appointment with a cardiologist in Guarda. These extremes not only occur in the countryside, as the waiting list for a neurological consultation at Amadora Sintra – one of the biggest state hospitals in the country – exceeds more than a year. The average waiting period for (non-acute) specialist care in Portugal is 4 months, varying from 6 months for an ophthalmologist to 6 weeks for an obstetrician. Patients who have to wait for more than five months have – by law – the right to be treated in the private sector. A costly buffer as the SNS, respectively the taxpayer must pay the bill.

The average waiting period for (non-acute) specialist care in Portugal is 4 months, varying from 6 months for an ophthalmologist to 6 weeks for an obstetrician. Patients who have to wait for more than five months have – by law – the right to be treated in the private sector. A costly buffer as the SNS, respectively the taxpayer must pay the bill. The excessive waiting lists are – according to the independent trade union of doctors Sindicato Independente dos Médicos – mainly the result of the fact that specialists in state hospitals have to spend too much – almost half – of their time to emergencies. The majority of the specialists working in the SNS is therefore unsatisfied. Many want to abandon the service and either go into private practice or leave the country, where working conditions are better and the pay higher.

The excessive waiting lists are – according to the independent trade union of doctors Sindicato Independente dos Médicos – mainly the result of the fact that specialists in state hospitals have to spend too much – almost half – of their time to emergencies. The majority of the specialists working in the SNS is therefore unsatisfied. Many want to abandon the service and either go into private practice or leave the country, where working conditions are better and the pay higher. ‘Wages are indeed low, excess hours abundant and career prospects nil’, explains Maria Ferreira of the Public Health Department of the University of Porto, who conducted an investigation under 15.000 doctors in northern Portugal. ‘Half of the recently qualified doctors is thinking of leaving the country after finishing their specialization and over 1200 doctors have already left in the past 3 years.’

‘Wages are indeed low, excess hours abundant and career prospects nil’, explains Maria Ferreira of the Public Health Department of the University of Porto, who conducted an investigation under 15.000 doctors in northern Portugal. ‘Half of the recently qualified doctors is thinking of leaving the country after finishing their specialization and over 1200 doctors have already left in the past 3 years.’ A draft legislation thereupon was submitted in July 2017 and discussed in Parliament early this year. Heloísa Apolónia – MP of the Ecological and Green Party (PEV) – explains ‘our proposal is to ban the use of plastic disposables in restaurants and bars and to look for biodegradable substitutes within 3 years.’

A draft legislation thereupon was submitted in July 2017 and discussed in Parliament early this year. Heloísa Apolónia – MP of the Ecological and Green Party (PEV) – explains ‘our proposal is to ban the use of plastic disposables in restaurants and bars and to look for biodegradable substitutes within 3 years.’ António Fonseca, the president of the Association of Bars in the Historic Center of Porto (ABZHP) – that encourages the legalization of the use of alcohol in public places – believes that the plans are irresponsible in the light of the danger glassware can cause in nightlife.

António Fonseca, the president of the Association of Bars in the Historic Center of Porto (ABZHP) – that encourages the legalization of the use of alcohol in public places – believes that the plans are irresponsible in the light of the danger glassware can cause in nightlife.

St. Martin’s Day is associated with the maturation of the year’s wine. It is a feast of Celtic roots that celebrates the end of summer and the start of winter.

St. Martin’s Day is associated with the maturation of the year’s wine. It is a feast of Celtic roots that celebrates the end of summer and the start of winter. Groups of friends and families celebrate these warm days in November outdoors and used to gather around a bonfire, where they roasted chestnuts directly in the fire drank água-pé (water-foot), jeropiga, new wine and danced and sang. It was customary for girls to bring the chestnuts and for boys to bring the wine.

Groups of friends and families celebrate these warm days in November outdoors and used to gather around a bonfire, where they roasted chestnuts directly in the fire drank água-pé (water-foot), jeropiga, new wine and danced and sang. It was customary for girls to bring the chestnuts and for boys to bring the wine. Água-pé (water-foot) is a light alcoholic beverage made by adding water to crushed grapes – after the juice is pressed out for wine – and letting it ferment for several days. Jeropiga – a sweet and strong fortified wine – is obtained in a similar way by adding brandy(aguardente) to the mash (pomace) of grapes, instead of water.

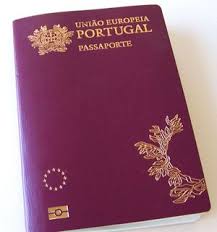

Água-pé (water-foot) is a light alcoholic beverage made by adding water to crushed grapes – after the juice is pressed out for wine – and letting it ferment for several days. Jeropiga – a sweet and strong fortified wine – is obtained in a similar way by adding brandy(aguardente) to the mash (pomace) of grapes, instead of water. For wealthy people, there is a far much easier way. Portugal’s ‘golden residence permit’ – visto gold – requires an investment of 500,000 euros in property in exchange for permanent residency and visa-free travel through Europe’s Schengen area.

For wealthy people, there is a far much easier way. Portugal’s ‘golden residence permit’ – visto gold – requires an investment of 500,000 euros in property in exchange for permanent residency and visa-free travel through Europe’s Schengen area. One of them is Otávio Azevedo, former president of Brazil’s second-largest construction company, Andrade Gutierrez. He received an 18-year sentence last year, after admitting a string of corruption offenses. Two years before his arrest he bought a € 1.4 million property in Lisbon and subsequently applied for a golden visa in 2014.

One of them is Otávio Azevedo, former president of Brazil’s second-largest construction company, Andrade Gutierrez. He received an 18-year sentence last year, after admitting a string of corruption offenses. Two years before his arrest he bought a € 1.4 million property in Lisbon and subsequently applied for a golden visa in 2014.