From symbol of modern technology during Salazar to symbol of revolution

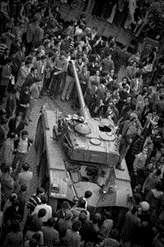

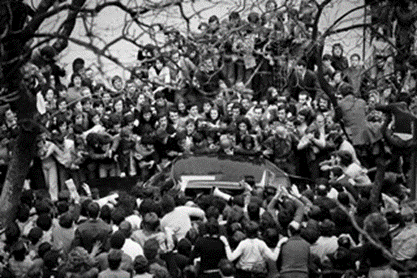

Fifty-one years on, revolutionary anthems will be sung again on the 25th of April when Portugal celebrates its Carnation Revolution, which in 1974 ended the Estado Novo (New State) of dictator António Oliveira Salazar, Europe’s longest-lasting dictatorship of more than forty years.

After an almost bloodless transition, a military junta promptly abandoned the unpopular colonial wars in three African countries (Angola, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique) and paved the way for democracy at home.

The carnations delivered 51 years ago to the military in Lisbon’s Largo do Carmo were produced in the Algarve at a time when Guilhermina Madeira was in charge of the CEAT (Tavira Agricultural Experimentation Center).

‘At that time we were the only ones producing carnations in the country. Flowers were sent on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays in a truck coming from Vila Real de Santo António to be sold at the Ribeira market in Lisbon’, she recalls.

It must have been there that the carnations were bought to celebrate the first anniversary of the restaurant where Celeste Caeiro worked, the woman who, in order not to spoil the flowers with the closure of the place due to the revolution in the streets, gave them to a soldier who put the carnation into the barrel of his gun.

‘They were carnations but could also have been tulips or gladioles, also produced at the time in the agrarian post’, Guilhermina, now 79 years old, admits with a smile. ‘Of course, those who made 25 April were the military and all those who fought for freedom but the flower eventually became the symbol of peace and freedom.’

‘In the late 60s all the varieties of flowers we had in the agrarian post were plants that did not exist in the area’, Guilhermina continues. ’The objective was to test the cultivation of the flowers to the conditions in the region’. The carnations – imported from Cap d’Antibes in the south of France – did very well. They were of the ‘American type’ with a large and elegant stem. We had whites, reds, orange and pink ones.’ She still remembers the trade names, from Scania red to Flamingo pink.

What once started as a ‘new technology and a symbol of modernity of Salazar’s Estado Novo with major investments in greenhouses and nurseries in Tavira to stimulate the flower production – which was very underdeveloped in Portugal – ended up becoming a ‘symbol of the end of the regime and the start of the revolution.’

Enjoy the party Aproveite a festa (pic Público/Sapo)