‘We hope a presidential candidate who includes everyone, will win’

The year 2025 was marked by setbacks in immigration issues, says Ana Paula Costa – president of the Casa do Brasil (Brazil’s House) in Lisbon – to newspaper Público. ‘We had a very difficult year in terms of narrative, legislation and integration of immigrants, not just for the Brazilian community.

‘Attacks of xenophobia and racism were unfortunately mainly directed to Asians and Roma but of course, the Brazilian community – being the largest in terms of numbers (nearly half a million Brazilians i.e. circa 5% of the Portuguese population) – was also greatly affected by this rhetoric’, she adds.

‘The impact of the rhetoric – in particular by André Ventura, chairman of the far-right party Chega – is direct on public services, on the way people are treated on a daily basis, on their rights and access. Immigration has been highly politicized in public discourse, and in a very negative way.’

In 2022, the Commission for Equality and against Discrimination (CICDR) reported that cases of xenophobia against Brazilians had increased exponentially, with reports of confrontations such as ‘it’s not my problem if you don’t know how to speak Portuguese’, ‘Brazilian women come here to steal our husbands’ and ‘you don’t understand anything, you’re stupid.’

A study by the Francisco Manuel dos Santos Foundation, published in 2024, indicated that five out of ten Portuguese citizens want the Brazilian presence in Portugal to decrease.

With the presidential elections later this month, Costa hopes that the Portuguese will elect someone who ‘values the rule of law, respects people and includes everyone in his mandate, as this is fundamental for democracy.’

In her assessment, the changes to the Foreigners Act (Lei de Estrangeiros) and the proposed amendments to the Nationality Act (Lei da Nacionalidade) have a clear objective of reducing the influx of immigrants. ‘The centre-right government demonstrates this on the argument of immigrant deregulation and lack of administrative capacity.’

‘But immigration was not deregulated,’ she explains! ‘Since the 1980’s we have had immigrant regulations in Portugal. And from an administrative capacity point of view, what happened is poor public administration, as is reflected in other public services, such as social security, health, housing and education, where there has been no investment over the years to enable people to exercise their rights, such as the right to obtain a valid residence permit in time.

‘In fact, this is a much bigger issue: there has been no investment whatsoever in the immigration service, and last year this has created huge administrative problems, especially in the transition from the Foreigners and Borders Service (SEF)to the Agency for Integration, Migration and Asylum (AIMA).’

So, less bureaucracy in public services, more recognition of the importance of immigrants, better regularization of immigration, less hate speech, and more jobs, political awareness, respect for fellow citizens and protection for women.

That’s the 2026 wish list of Brazilians in Portugal.

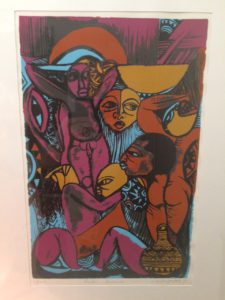

Happy New Year Feliz Ano Novo (Pic Público/Sapo)

Both left and right wing parties in Parliament are concerned about racism in the police force and violation of human rights in prisons. The reason is a recently published report of the European Committee against Torture, stating that police violence in Portugal – in particular against African descendants – is the highest in Western Europe.

Both left and right wing parties in Parliament are concerned about racism in the police force and violation of human rights in prisons. The reason is a recently published report of the European Committee against Torture, stating that police violence in Portugal – in particular against African descendants – is the highest in Western Europe. The committee – that also visited the country in 2013 – emphasizes that the police violence at police stations has increased and that the situation in the overcrowded prisons of Caxias, Setubal, and Lisbon is ‘inhuman and degrading.’

The committee – that also visited the country in 2013 – emphasizes that the police violence at police stations has increased and that the situation in the overcrowded prisons of Caxias, Setubal, and Lisbon is ‘inhuman and degrading.’ Julia Kozma, lawyer and chairing the European delegation, points the finger towards the Ministry of Internal Affairs – responsible for the police and the security forces – and regrets its lack of ‘awareness’. The Ministry denies the accusations and declares that ‘all complaints about violent police conduct are investigated by the Internal General Inspectorate (IGAI) and immediately reported to the Public Prosecutor.’

Julia Kozma, lawyer and chairing the European delegation, points the finger towards the Ministry of Internal Affairs – responsible for the police and the security forces – and regrets its lack of ‘awareness’. The Ministry denies the accusations and declares that ‘all complaints about violent police conduct are investigated by the Internal General Inspectorate (IGAI) and immediately reported to the Public Prosecutor.’ The reality, however, is that only a very small number of the complaints are brought before court. ‘And that’s exactly the problem’, says Kozma. ‘There is a spirit of impunity and bureaucracy, whereby complaining doesn’t help. The inspection body (IGAI) needs more skills to conduct criminal investigations and more resources to act independently.’

The reality, however, is that only a very small number of the complaints are brought before court. ‘And that’s exactly the problem’, says Kozma. ‘There is a spirit of impunity and bureaucracy, whereby complaining doesn’t help. The inspection body (IGAI) needs more skills to conduct criminal investigations and more resources to act independently.’ In recent months the non-governmental organization SOS racism received an increasing number of grievances from inmates in the prison of Lisbon about racist provocations and intimidations. Peculiar was that all complaints came from African immigrants and that any registration on xenophobe or racist behavior from the guards and staff is lacking.

In recent months the non-governmental organization SOS racism received an increasing number of grievances from inmates in the prison of Lisbon about racist provocations and intimidations. Peculiar was that all complaints came from African immigrants and that any registration on xenophobe or racist behavior from the guards and staff is lacking. Mamadou Ba is born in Senegal and has the Portuguese nationality. He is graduated, has a steady job at the Parliament, and speaks with a slight African accent. When he is calling for an apartment in Lisbon’s Parque das Nações neighborhood, he gets an appointment 2 days later. Although the tenant promises him to send an SMS with additional information, he never does. If shortly thereafter a journalist of the newspaper Público– with a Portuguese name and a Lisbon accent – calls the same tenant, he immediately gets the necessary information by phone and an appointment for the next day. In only two out of five phone calls, Mamadou and the journalist were treated the same way.

Mamadou Ba is born in Senegal and has the Portuguese nationality. He is graduated, has a steady job at the Parliament, and speaks with a slight African accent. When he is calling for an apartment in Lisbon’s Parque das Nações neighborhood, he gets an appointment 2 days later. Although the tenant promises him to send an SMS with additional information, he never does. If shortly thereafter a journalist of the newspaper Público– with a Portuguese name and a Lisbon accent – calls the same tenant, he immediately gets the necessary information by phone and an appointment for the next day. In only two out of five phone calls, Mamadou and the journalist were treated the same way. ‘It isn’t true that social class eliminates racism.

‘It isn’t true that social class eliminates racism. ‘These numbers are shocking’, says Alípio Ribeiro, an attorney from the Criminal Investigation Department and confirm what he already thought: ‘there is a legal system for whites and a legal system for blacks’.

‘These numbers are shocking’, says Alípio Ribeiro, an attorney from the Criminal Investigation Department and confirm what he already thought: ‘there is a legal system for whites and a legal system for blacks’. Celso Manata, head of DGPJ, however, rejects the idea that the legal system is discriminatory. He admits that there is an over-representation of blacks in Portuguese prisons, but believes that ‘this is caused by the poor socio-economic circumstances of black people, who therefore are more likely to commit a crime’.

Celso Manata, head of DGPJ, however, rejects the idea that the legal system is discriminatory. He admits that there is an over-representation of blacks in Portuguese prisons, but believes that ‘this is caused by the poor socio-economic circumstances of black people, who therefore are more likely to commit a crime’. Het Openbaar Ministerie heeft – na 2 jaar onderzoek – 18 politieagenten beschuldigd van raciaal geweld, ernstig letsel, marteling, valsheid in geschrifte en ontvoering van 6 jonge Afro-Portugezen in Cova de Moura, een van de oudste en grootste achterstandswijken van Lissabon, met 7000 inwoners, de meeste afkomstig uit Kaapverdië.

Het Openbaar Ministerie heeft – na 2 jaar onderzoek – 18 politieagenten beschuldigd van raciaal geweld, ernstig letsel, marteling, valsheid in geschrifte en ontvoering van 6 jonge Afro-Portugezen in Cova de Moura, een van de oudste en grootste achterstandswijken van Lissabon, met 7000 inwoners, de meeste afkomstig uit Kaapverdië. Als ze – na voorgeleid te zijn aan de onderzoeksrechter in Sintra – bij gebrek aan bewijs vrij komen, doen ze aangifte van marteling en racistisch geweld. Intern onderzoek bij de politie levert daarvoor onvoldoende aanwijzingen op en twee agenten worden licht gestraft – een wordt overgeplaatst en de ander 6 maanden geschorst. De overige blijven gewoon dienst doen in de wijk.

Als ze – na voorgeleid te zijn aan de onderzoeksrechter in Sintra – bij gebrek aan bewijs vrij komen, doen ze aangifte van marteling en racistisch geweld. Intern onderzoek bij de politie levert daarvoor onvoldoende aanwijzingen op en twee agenten worden licht gestraft – een wordt overgeplaatst en de ander 6 maanden geschorst. De overige blijven gewoon dienst doen in de wijk. ‘Institutioneel racisme wordt in stand gehouden door een van de grootste leugens die we onszelf voorhouden, namelijk dat Portugal in het – koloniale – verleden amper racistisch geweest is’, zegt Joana Mortágua, parlementslid van het Links Blok. ‘Dat belemmert integratie.’ [

‘Institutioneel racisme wordt in stand gehouden door een van de grootste leugens die we onszelf voorhouden, namelijk dat Portugal in het – koloniale – verleden amper racistisch geweest is’, zegt Joana Mortágua, parlementslid van het Links Blok. ‘Dat belemmert integratie.’ [