Today, Lisbon tops Europe’s housing unaffordability ranking

Unaffordable house prices and rents are a continent-wide concern. Over the past decade, house prices in the EU rose by 50% on average, and rents by 18%. Housing policy has favoured those who invest in homes at the cost of those who live in them. Across Europe, property has become a driving force of inequality.

During that same period, Lisbon has undergone a dramatic transformation, from one of the most affordable capitals in Europe to one of the most unaffordable. House prices rose by more than 200% in its central historical district. This trend is extending to the national level. In 2015, Portugal ranked 22nd out of 27 EU countries for housing unaffordability. Today it ranks first!

To understand how Lisbon reached this point, we have to go back to the 2008 global financial crisis, after which the country embraced a strategy of aggressive liberalization, in order to entice foreign real estate investment.

Rental laws were relaxed, making evictions easier and tenancy agreements shorter. Generous tax-incentives were introduced for non-resident buyers, including the controversial ‘golden visa’ and ‘non-habitual resident’ programmes. At the same time, both the hotel industry and the short-term rental sector were promoted.

In the historic centre of Lisbon, Airbnb rentals have reached dramatic levels: half of all homes hold a short-term licence, and in the most tourist-saturated neighbourhoods, that figure even climbs to 70%.

When measured against the city population, this number represents a density 6 times higher than in Barcelona and 3 times higher than in London. Meanwhile, the number of hotels has tripled – from around 100 to 300 – and there already exist approved plans for 50 more.

These changes happened in a global context of low interest rates in which affluent people increasingly turned to housing as a place to park their savings. Storing of wealth in housing drives up prices; the medium of transactions made by foreign buyers in Lisbon is 80% higher than the price paid by domestic buyers, whereas the country stands out for its overvaluation of house prices by 35%.

The result is a city that welcomes foreign wealth but excludes many of its own citizens, prioritizing the desires of the global consumers over the needs of the local community. Beyond an increasing number of tourists, central Lisbon is now primarily occupied by a transnational class of mobile young professionals and digital nomads from other countries, whereas local middle-class people are being pushed out to the suburbs or forced to adapt by renting rooms instead of apartments.

At the same time, a growing share of the income – half of the Portuguese taxpayers earn less than 1000 euros a month – is being consumed by housing costs, deepening social inequality. Citizens in Lisbon spend the highest percentage of their salary on housing in the EU.

Contrary to the neoliberal myth that the market alone can meet the needs of the population, Lisbon offers another example of market failure, dividing society and fuelling the popularity of far-right parties like Chega.

‘ We’re running the risk of having the working and middle classes conclude that their democracies are incapable of solving their biggest problem,’ the mayor of Barcelona recently declared.

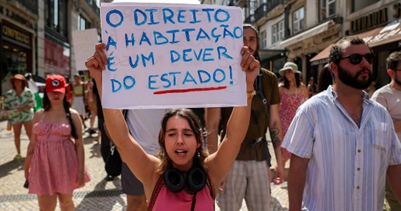

Happy reading Boas leituras (Pic PtRes/Lusa)

‘No, it is not okay’, mutters João. ‘We got a letter from the landlord the other day. Our contract expires in November. He wants to increase the rent from 300 to 800 euro a month and reduce the contract period to one year. I’ am sure he’ll increase the rent again next year.

‘No, it is not okay’, mutters João. ‘We got a letter from the landlord the other day. Our contract expires in November. He wants to increase the rent from 300 to 800 euro a month and reduce the contract period to one year. I’ am sure he’ll increase the rent again next year. ‘Where do you live?’, I ask

‘Where do you live?’, I ask Within five years rents in Lisbon increased by 36%.

Within five years rents in Lisbon increased by 36%. Housing is a priority for this government, that wants to build more affordable accommodation and has set aside 1,7 billion euros to give 26.000 needy families – half of them from Lisbon – a decent home within six years. It also intends to give municipalities the right to claim vacant properties for social habitation.

Housing is a priority for this government, that wants to build more affordable accommodation and has set aside 1,7 billion euros to give 26.000 needy families – half of them from Lisbon – a decent home within six years. It also intends to give municipalities the right to claim vacant properties for social habitation. Well, it’s a pity I’ am not one of those families and six years is a long time, especially at my age’, João replies.

Well, it’s a pity I’ am not one of those families and six years is a long time, especially at my age’, João replies.