‘It is not just about administering methadone, you have to maintain a relationship’

In 2001 Portugal became – under the leadership of prime minister António Guterres, nowadays UN’s Secretary-General – the first country to ‘decriminalize’ the possession and consumption of illicit substances, even heroin, and cocaine.

In 2001 Portugal became – under the leadership of prime minister António Guterres, nowadays UN’s Secretary-General – the first country to ‘decriminalize’ the possession and consumption of illicit substances, even heroin, and cocaine.

Despite predictions at the time of an increase in drug use and drug tourism by opponents of decriminalization, the opposite happened with huge drops in drug use, overdose deaths, drug-related crime, and HIV infection. New cases of HIV among people who inject drugs (PWID) fell from 907 in 2000 – when the country had the highest rate of HIV among PWID in Europe – to just 18 in 2017.

Despite predictions at the time of an increase in drug use and drug tourism by opponents of decriminalization, the opposite happened with huge drops in drug use, overdose deaths, drug-related crime, and HIV infection. New cases of HIV among people who inject drugs (PWID) fell from 907 in 2000 – when the country had the highest rate of HIV among PWID in Europe – to just 18 in 2017.

The country’s policy rests on 3 pillars: (i) there is no distinction between so-called soft and hard drugs, (ii) an individual’s unhealthy relationship with drugs often masks unsatisfactory relationships with the world around and (iii) the eradication of all drugs is an impossible goal.

The country’s policy rests on 3 pillars: (i) there is no distinction between so-called soft and hard drugs, (ii) an individual’s unhealthy relationship with drugs often masks unsatisfactory relationships with the world around and (iii) the eradication of all drugs is an impossible goal.

What did and what did the country not do?

What did and what did the country not do?

It did not change laws on drug trafficking: dealers still go to prison. And it did not ‘legalize’ drug use but rather made the purchase or possession of small quantities (up to a 10 day supply) not a crime.

Methadone clinics, clean needle handouts, supervised injection sites, drug consumption facilities and a pan-ministerial network of support were set up and are still operational today.

There are currently two Threshold Mobile Units in Lisbon – attending approximately 1,200 people a day – and 170 recovery facilities in a country of 10 million people for treatment and education about the harmful effects of drugs.

There are currently two Threshold Mobile Units in Lisbon – attending approximately 1,200 people a day – and 170 recovery facilities in a country of 10 million people for treatment and education about the harmful effects of drugs.

This public health approach reflects the view that addiction is more a medical challenge than a criminal justice issue; a chronical disease that requires medical care rather than punishment. An additional benefit of the Portuguese model is that it’s far cheaper to treat people than to jail them.

While other states have developed various forms of de facto decriminalization – whereby substances perceived to be less harmful (such as cannabis) rarely lead to criminal prosecution – Portugal remains the only EU member state with a law explicitly declaring drugs to be ‘decriminalized.’

While other states have developed various forms of de facto decriminalization – whereby substances perceived to be less harmful (such as cannabis) rarely lead to criminal prosecution – Portugal remains the only EU member state with a law explicitly declaring drugs to be ‘decriminalized.’

Bom fim de semana Enjoy the weekend (pic Público/NYT/Cato)

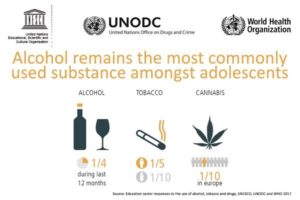

What does this mean for the health of the Portuguese? Excessive alcohol intake is associated with road traffic accidents, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, domestic violence, and suicide attempts.

What does this mean for the health of the Portuguese? Excessive alcohol intake is associated with road traffic accidents, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, domestic violence, and suicide attempts.

Given the fact that there is no

Given the fact that there is no