‘Where 2 dogs fight for a bone, the 3rd runs away with it home’ – Dutch saying

A 50-year-old political system dominated by two main parties – the centre-right Social Democratic Party (PSD) and the Socialist Party (PS) – has come to an end as the far-right party Chega (Enough) picked up nearly one-fifth of the votes on anti-corruption, immigration and euroscepticism.

The Democratic Alliance (AD) – a centre-right coalition of the PSD and the Christian Democrats led by Luis Montenegro – technically won the elections with 29% of the votes. The margin, however, was only 1% with their main opponent, the centre-left PS. It is very unlikely that the two main parties will cut a deal, leaving the centre-right facing an unstable minority government.

The elections brought an end to the nine-year government of the Socialist Party of António Costa, who had to resign last November as a result of alleged illegalities in his government’s handling of large green investment projects. His Partido Socialista only took 28% of the votes, a dramatic fall since the comfortable victory in 2022 with 47% of the votes. After losing the election the current party leader Pedro Nuo Santos declared that the PS would lead the opposition.

The far-left also fared badly with an increasingly weak Communist party (PCP) securing just four MPs and the anti-capitalist Left Bloc (BE), clasping to the five seats it has since 2022. The pro-EU party Livre was more lucky, going from one to four MPs.

The biggest win, however, went to the populist Chega party, led by former football commentator Andre Ventura. It became the 3rd political party in the country with 18% of the votes after obtaining a mere 7% of the votes in 2022.

Corruption ranks high among voters’ concerns and was a key focus of the far-right campaign. Besides the investigation into Costa’s administration that triggered this election, another former Socialist prime minister – José Sócrates – is going to stand trial again over allegations that he pocketed about 34m euros during his time in power from fraud and money laundering. But also the PSD is facing corruption allegations, with two prominent party politicians recently forced to resign amid a fraud investigation in Madeira.

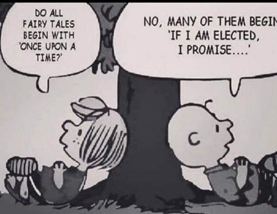

It is unclear what role the far-right party will play in the new government since AD’s party leader Montenegro has repeatedly declared that he refuses to cut a deal with the ‘racist, xenophobic and demagogic’ Chega leader Ventura. The question is now how much strength is left in that cordon sanitaire.

Chega’s success is the result of letting the social discontent grow on deteriorating living and working conditions. Costa’s majority government proved to be unable to meet the economic aftermath of Covid. Minimum wage increases unable to meet inflation, rent controls out of the question, and faltering performance in public education and the National Health Service (SNS).

In the westernmost nation of mainland Europe where incomes are the sixth lowest in the EU, over 10% of the population are living in food poverty and ‘non-habitual residents’ (i.e. expats) enjoy considerable tax exemptions, people are easy prey to an ultra-nationalist party that promises higher wages and public spending but lower taxes at the same time.

Have a nice week Tenha uma semana boa (pic Público/Sapo)