‘Portugal is becoming a country of minimum wages’

Joana Gonçalves is 47 years old and works for 20 years as an operating assistant at the same hospital. Last year she earned 665 euros per month, just as much as the minimum wage. Deducting € 103,08 for Social Security and adding a food allowance of € 81.09, her net salary was 643,01 euros. Fifteen years ago Ana earned € 580, while the minimum wage was 430 euros. In the meantime, salaries have been frozen as a result of austerity measures while minimum wages increased. Her daughter Maria had to drop out of university because Joana had no longer money to support her. Maria is now cleaning in a supermarket.

Minimum wages in the EU member states range from € 332 per month in Bulgaria to € 2257 euros in Luxembourg. Since the Socialist Government of António Costa seized power in 2015, the minimum wage has increased by 40% to € 705 this year. Average salaries, however, have only increased 10% during the same period.

‘This neglect to update the salaries of more qualified workers has caused strong distortions in the country. Nowadays more and more workers receive a salary very close to the minimum wage’, says economist Eugénio Rosa, advisor to the Confederation of Portuguese Workers (CGTP). ‘Portugal is transforming into a country of minimum wages’.

The IEFP (Institute of Employment and Professional Training) proves the point. Of the 150 job vacancies on its site – aimed at civil engineers, electro technicians, mechanics, etc – the majority of salaries offered vary between €750 and €1000.

‘But it’s anything but easy to get out of this trap’, explains Fernando Alexandre, professor at the School of Economics from the University of Minho in Braga.

‘Not only is our minimum wage one of the lowest in Europe, our country was last year one of the EU countries with the lowest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, the country’s wealth-producing capacity per worker. Only Bulgaria was doing worse’.

To make matters worse, the pandemic has condemned hundreds of thousands of Portuguese into poverty. These ‘new poor’ are almost all people who already earned a minimum wage – or even less – before the pandemic. Workers in the tourism sector, restaurants, and hospitality were most hit by the restrictions to contain the pandemic. Women – especially the elderly – are among the most affected.

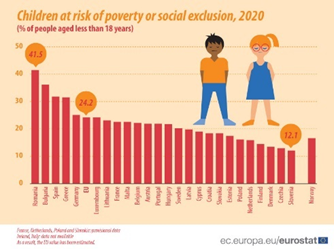

The bottom line is that today one in five Portuguese is at risk of poverty. In children, the risk is even greater (22%). Food banks have become indispensable. There are more than 2000 institutions – parishes and councils identifying the populations’ needs – which have partnerships with the 21 food banks that are feeding approximately 450.000 persons (4% of the population).

Enjoy your week Aproveite a semana (pic Público/Sapo)

Obesity is Portugal’s biggest Public Health problem

Obesity is Portugal’s biggest Public Health problem  ‘That social inequality has an impact on health is beyond doubt.

‘That social inequality has an impact on health is beyond doubt. The average Portuguese eats for two, meaning almost 4000 calories per person per day!

The average Portuguese eats for two, meaning almost 4000 calories per person per day! As a result of the obesity epidemic diabetes is very common and Portugal even has the highest prevalence of diabetes in Europe. One in every 7 citizens is affected and 25% of the people – who die in hospital – have diabetes. The risk to get the disease is four times higher in people, who haven’t completed primary school – a number twice as high in Portugal, than elsewhere in Europe.

As a result of the obesity epidemic diabetes is very common and Portugal even has the highest prevalence of diabetes in Europe. One in every 7 citizens is affected and 25% of the people – who die in hospital – have diabetes. The risk to get the disease is four times higher in people, who haven’t completed primary school – a number twice as high in Portugal, than elsewhere in Europe.